Strangling India's Silk Industry

Silk's smooth, but its industry in India has some serious rough patches!

At ReadOn, we don’t just report the markets. We help you understand what truly drives them, so your next decision isn’t just informed, it’s intelligent.

Here’s a riddle. What do you get when a silkworm spins its cocoon, but bureaucrats spin their files even slower?

Answer: A lot of wasted silk.

Earlier this month, India’s Ministry of Textiles amended a 70-year-old rule that most people have never heard of. Rule 22 of the Central Silk Board Rules, 1955, now allows the Board to approve projects worth up to ₹1 crore on its own. Earlier, the limit was ₹50 lakh. Anything above that had to crawl its way to Delhi for ministerial clearance, which could take months, sometimes years.

You might wonder, “Why does this matter? It’s just an approval threshold, right?”

Well, not quite. Because in the silk business, time isn’t just money. It’s biology.

The 15-Day Window

Silk has very strict requirements. Once a silkworm spins its cocoon, the yarn must be extracted within about 15 days. Miss that window, and the thread loses its sheen, its strength, and its market value. The entire crop, essentially, goes from premium to scrap.

Now picture this. A state sericulture department wants to set up a mechanised reeling unit in a cluster of villages. The project costs ₹80 lakh. Under the old rule, ₹50 lakh could be approved locally. But the remaining ₹30 lakh? That had to be referred to the Ministry of Textiles in New Delhi. Weeks of paperwork. Months of waiting. Meanwhile, the silk season came and went. Farmers continued using outdated equipment. Quality suffered. Exports stalled.

This isn’t a hypothetical scenario. Industry insiders say it happened all the time.

The absurdity? That ₹50 lakh cap hadn’t been revised in decades. It was set when ₹50 lakh actually meant something substantial. Over the years, as project costs ballooned due to new technology, inflation, more ambitious schemes, the ceiling stayed frozen in time. Planners began designing projects around the constraint, splitting large initiatives into smaller sub-projects just to avoid the Delhi route. A ₹90 lakh seed laboratory would become two ₹45 lakh proposals with separate timelines, separate contractors, and often inconsistent outcomes.

The tail was wagging the worm, so to speak.

India’s Silk Paradox

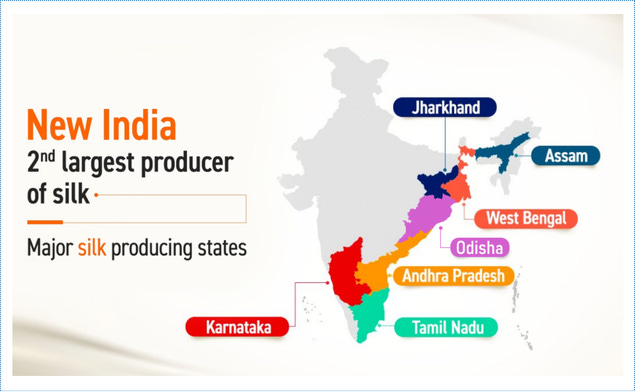

Now, things get interesting. India is the world’s second-largest producer of raw silk, after China. It’s also the world’s largest consumer. The country produces all four commercial varieties (Mulberry, Tropical & Oak Tasar, Muga, and Eri), making it the only nation to do so. Karnataka has mulberry belts, Assam has Muga heritage, and Odisha has Tussar traditions. Silk runs deep in India’s cultural and economic fabric. The domestic market is, as industry folks put it, “culture-bound”, or focused around weddings, festivals, religious ceremonies. These drive steady demand for silk sarees and textiles.

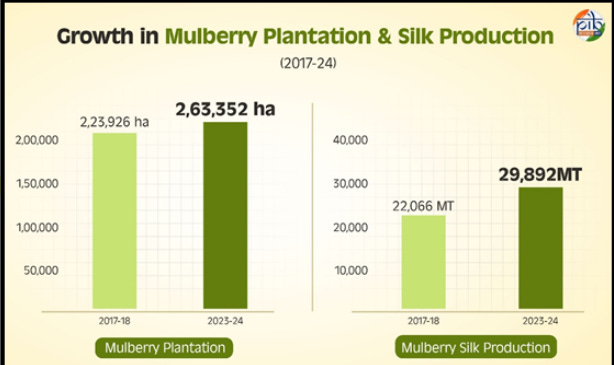

The numbers look impressive on paper. In FY25, India produced about 41,121 metric tonnes of raw silk. Mulberry silk dominated the output, followed by Eri, Tasar, and the prized Muga at a very small percentage. Mulberry area expanded nearly 18% between 2017 and 2024, and raw silk production grew by 35% over the same period.

And yet, India still imports over $150 million worth of raw silk every year. In 2023, the country brought in about 27.8 lakh kilograms of raw silk. Primarily from Vietnam ($96 million) and China ($59 million). Why? Because domestic production, especially of finer bivoltine grades, doesn’t fully meet demand. Indian farms churn out mostly lower-grade multivoltine cocoons. The high-filature silk that global markets crave, or the 3A-grade stuff that fetches premium prices in Europe and Japan? That often comes from abroad.

There’s another problem. India exported about 3,348 metric tonnes of silk waste in FY2023-24. These are the leftover bits and coarse fibre from inefficient reeling. That’s value literally being shipped out as scrap because reeling infrastructure hasn’t kept pace with production growth.

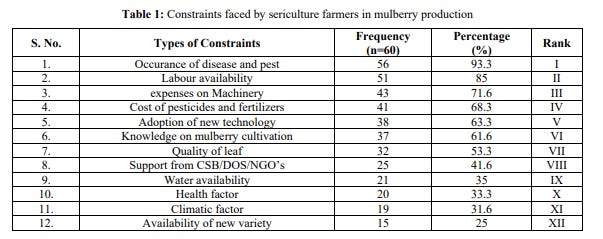

The entire value chain is riddled with gaps. Silkworm seeds of inconsistent quality. Pest outbreaks that affect 93% of mulberry rearers in Karnataka, according to one study. Labour shortages (silkworm rearing is notoriously labour-intensive and timing-sensitive). Outdated reeling machines that waste silk instead of saving it. Limited access to credit for small weavers. Fragmented marketing with weak global branding. And above it all, bureaucratic inertia that slowed down every attempt to fix these problems at scale.

What the ₹1 Crore Fix Actually Enables

The January 2026 notification isn’t about throwing more money at the silk sector. The Central Silk Board’s budget remains the same. This is about how that money gets spent.

With the ₹1 crore ceiling, the Board can now green-light a whole category of projects that were previously stuck. Think of a modern common facility centre with mechanised reeling machines and testing equipment. Its cost? ₹80–90 lakh. Earlier, that would’ve needed ministerial approval. Now it doesn’t.

Or consider the CSB’s push for digital initiatives. Like the SILKS portal, real-time price information via mobile platforms, traceability systems, etc. Upgrading these IT tools can now be sanctioned faster. Multi-state weaver training centres, regional seed laboratories, integrated pest management facilities, all of these can now proceed as single, coherent projects instead of being chopped into bureaucratic-friendly fragments.

The reform also sends a broader signal. By empowering the CSB to act more autonomously, the government is acknowledging that specialised statutory bodies should be trusted to move faster.

But Let’s Not Get Carried Away

The ₹1 crore fix is welcome. But it’s not a silver bullet.

For one, it doesn’t address the fundamental resource adequacy problem. If the CSB’s annual budget is ₹300 crore, that sum isn’t increasing because of this rule change. The ceiling just allows existing funds to be allocated more efficiently.

Second, many of sericulture’s problems lie outside the Board’s purview. Pest outbreaks, weather disruptions, soil health, labour migration. These require sustained extension work, R&D investment, and coordination with state governments. The CSB can approve projects faster now, but it still needs states to implement them on the ground. Historically, even when central funds were approved, execution at the state level lagged.

Third, the downstream challenges persist. Indian silk still struggles with global branding, design development, and compliance with international standards. Investors in the sector need trade agreements, freight subsidies, and buyer linkages. These are areas the CSB doesn’t control.

And then there’s the elephant in the room. Competition from synthetic fibres. Silk accounts for just 0.2% of global textile output. As disposable incomes rise, will younger consumers pay a premium for silk, or opt for cheaper alternatives or maybe vegan silk? That’s a question no bureaucratic reform can answer.

The Bigger Picture

The silk reform is small in scale but symbolic in significance. Traditional sectors like silk, handlooms, coir, and fisheries often get lost in the shadow of big-ticket industries. They’re fragmented, rural, and biologically complex. They don’t attract headlines or unicorn valuations.

But they employ lakhs and crores. Sericulture alone supports nearly 1 crore people. Thinks farmers, reelers, weavers, traders, mostly in rural India. These are livelihoods that hinge on the kind of nimble governance that a ₹1 crore approval ceiling represents.

If this pilot succeeds, other legacy sectors might draw lessons. The Coir Board, the Khadi Commission, the National Handloom Corporation all have their own approval bottlenecks and archaic rules. The silk sector’s experience could prompt a broader review of how India governs its traditional industries.

And that, perhaps, is the real silk thread worth following.

In other news, have you been checking out the crosswords below these articles? Try them out for yourselves, and see how quickly you can solve them!

Until next time, ReadOn!

ReadOn Insights Crossword 23-01-2026

Hints:

Across:

2: An Arctic island at the centre of growing strategic, mineral, and geopolitical competition.

6: The strategic naval chokepoint between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom.

8: The indigenous population forming roughly 90% of Greenland’s residents.

9: A US space base in Greenland that is critical for missile early-warning and space surveillance systems.

10: The country that currently holds sovereignty over Greenland, which operates as an autonomous territory.

Down:

1: The US president who stated in January 2025 that America “must” have Greenland.

3: The capital of Greenland, where the United States reopened its consulate in 2020.

4: The military alliance actively monitoring Arctic sea routes and operating in Greenlandic airspace.

5: Which country has declared itself a “near-Arctic state” and is pursuing the Polar Silk Road strategy.

7: A rare-earth deposit considered among the largest in the world, with strategic importance for clean-energy supply chains.

To solve this puzzle, click here!