Social commerce: The Trust Gap Kills Scale

Why is this "China ka maal" struggling in India?🤔

At ReadOn, we don’t just report the markets. We help you understand what truly drives them, so your next decision isn’t just informed, it’s intelligent.

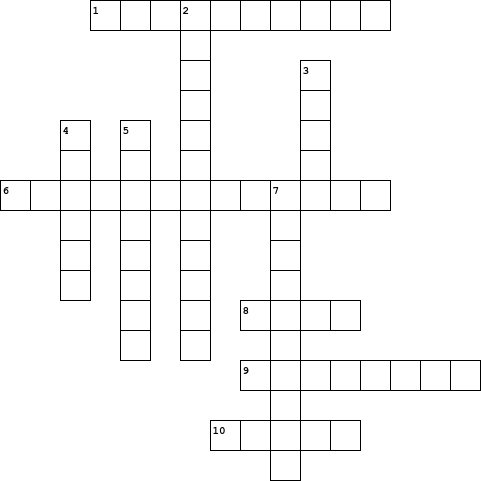

Social commerce, or e-commerce with aspects of social media blended in, contributes nearly a third of all online retail sales in China. In Indonesia, the figure hovers around 20-25%. In India? It’s stuck at 1-2%.

That single data point tells you almost everything you need to know about how the much-hyped social commerce wave has played out in this country. For years, investors and founders have chased the dream of replicating China’s success. The livestream shopping bonanzas, the viral group-buying deals, the influencer-led product discovery that turned platforms like Pinduoduo into $170 billion behemoths. India, with its massive smartphone user base and WhatsApp-addicted population, seemed like the obvious next frontier.

The global numbers certainly looked encouraging. Social commerce crossed $1.6 trillion worldwide in 2024 and is expected to grow at 30% annually through 2030. China alone accounts for roughly $900 billion of that pie, with over 500 million people (or half the country’s internet users) regularly watching livestream shopping. WeChat, with 1.3 billion monthly active users, has evolved into a super-app where commerce, communication, and payments blend seamlessly.

India’s reality has been rather different.

What Social Commerce Actually Means

The term gets thrown around loosely, but social commerce generally works through three distinct models.

Livestream shopping involves real-time video broadcasts where hosts demonstrate products while viewers watch, interact, and purchase simultaneously. Influencer-led commerce relies on creators showcasing products on platforms like Instagram or YouTube, driving followers toward purchases. Group buying aggregates consumers, who purchase together to unlock volume discounts. This is the model that made Pinduoduo a household name in China.

Indian startups have attempted all three. Simsim built a video shopping platform targeting women’s fashion; YouTube acquired it and later shut it down. DealShare adopted the Pinduoduo playbook for groceries and essentials, reaching unicorn status with around $600 million in annual revenue, but many others stumbled. GlowRoad built networks of women resellers curating WhatsApp catalogues; Amazon acquired it for approximately $75 million, though it never achieved mainstream scale.

The pattern is consistent. Promising starts, followed by pivots, shutdowns, or modest outcomes.

Meesho: Success, With Asterisks

If any company represents Indian social commerce, it’s Meesho. Founded in 2015, the platform enabled millions of resellers (predominantly women in smaller towns) to browse product catalogues, share images via WhatsApp, collect orders from their personal networks, and earn margins on each sale. Meesho handled logistics and payments. The reseller provided the trust.

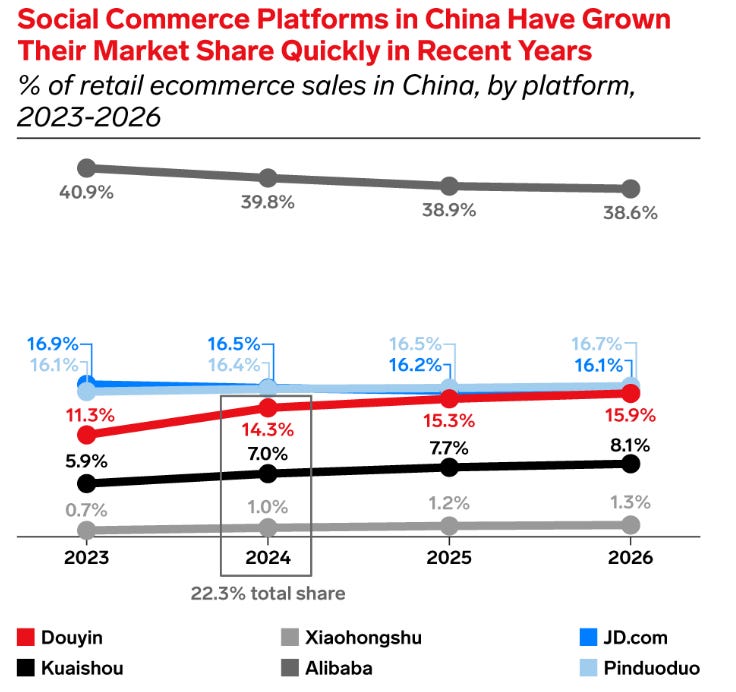

The model found genuine traction. By FY25, Meesho reported over 205 million monthly active users and gross merchandise value exceeding ₹50 thousand crore. More than 95% of its catalogue consists of unbranded fashion and homeware priced between ₹100-300. It’s the kind of affordable everyday goods that resonate with price-conscious buyers in tier-2 and tier-3 India.

But profitability remains elusive. Meesho posted a net loss of ₹3,942 crore in FY25. For context, Pinduoduo, which was founded the same year, was solidly profitable by its seventh year and has reported multi-billion dollar annual profits since 2023.

More significantly, Meesho has gradually shifted away from its original social-first model toward functioning as a conventional e-commerce marketplace. The reseller network still exists, but the platform increasingly resembles its horizontal competitors. That pivot itself signals how difficult pure social commerce has proven in this market.

Flipkart’s Shopsy followed a similar trajectory. Launched in 2021 as a social sharing platform where users earned commissions for referring products, it crossed 100 million registered users within a year, with 70% coming from smaller towns. The platform now lists 150 million products, 60% priced under ₹200. Flipkart credits Shopsy with contributing 40% of its new first-time buyers. Yet Shopsy too has evolved into more of a value-commerce marketplace than a social-driven platform.

There are smaller bright spots. Myntra now generates 10% of its revenue through social commerce, working with 3.5 million creators. Hindustan Unilever has scaled its influencer collaborations from 700 to 12,000 in a single year. These experiments suggest brands see value in the channel.

The Structural Barriers

But why does social commerce thrive in China but sputter in India? The obstacles are deeper than funding or execution.

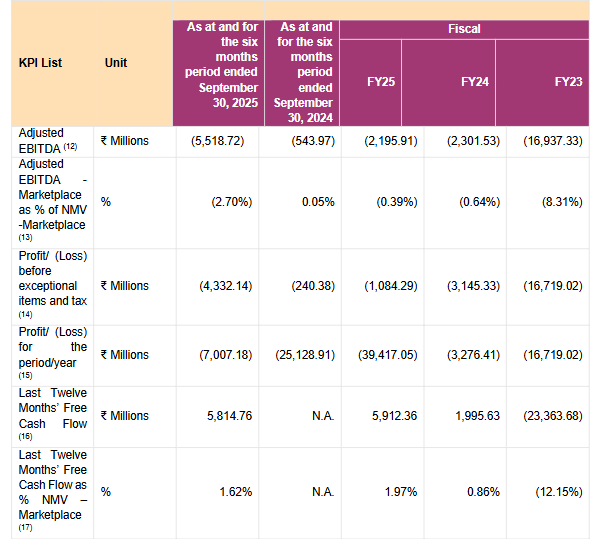

Consider trust. A survey by Integrated Values Surveys found that roughly 60% of people in China believe most others can be trusted. In India, that figure drops to around 20%. This shapes purchasing behaviour directly. Chinese consumers routinely pay upfront via digital wallets and cards. Indian consumers, particularly outside metros, prefer inspecting products before parting with money. Research from IIM Ahmedabad indicates that nearly 65% of e-commerce purchases in tier-2 cities still happen through cash-on-delivery. These transactions don’t necessarily happen in cash. Customers use UPI or cash, but that preference creates working capital challenges for platforms and undermines the frictionless experience social commerce requires.

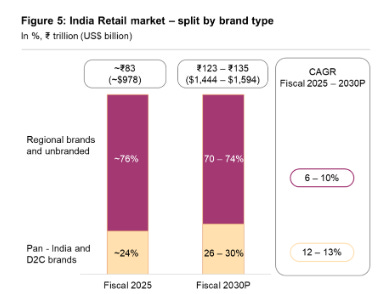

Economics compound the problem. Average order values in India run 2-3 times lower than China’s. When customers are buying ₹200 kurtis with thin reseller margins, and platforms must absorb delivery costs and handle high return rates, unit economics become punishing. India’s retail landscape also remains extraordinarily fragmented. Regional brands and unbranded products account for over 75% of total retail spending. Standardising offerings the way Chinese platforms do is nearly impossible.

Also, many first-time online shoppers in India are wary due to limited protection and fear of fraud. Although regulations require easy returns and authentic products, enforcement is uneven. High return rates (quoted up to 40–50% in some cases) deter some companies from providing heavy discounts.

Then there’s the regulatory environment around content credibility. China’s Cyberspace Administration mandates that creators provide proof of qualifications like degrees, licences, certified training, etc. before posting content on sensitive topics like health or finance. Platforms like Douyin actively verify these credentials. In India, disclosure requirements apply only to technical advice, not general awareness content. Creators face no qualification requirements for sharing health tips or financial guidance. The predictable result is widespread misinformation, which further erodes consumer trust in social platforms as shopping destinations.

The Road Ahead

Will social commerce in India eventually catch up? Growth will likely outpace traditional e-commerce, but that’s not saying much when you’re starting from 1-2% of the market. Projections suggest Indian social commerce could reach $13-14 billion by 2030, healthy expansion from the current $7-8 billion, but still a rounding error compared to China’s scale.

Reaching Chinese levels of maturity, where social commerce represents 30-40% of online retail would require transforming India’s trust ecosystem, building frictionless payment habits, achieving logistics density that doesn’t exist today, and creating content regulation that establishes credibility. Each of these is a multi-year undertaking. Together, they represent at least a decade of infrastructure building.

WhatsApp remains the most intriguing variable. With over 400 million Indian users, it’s the closest approximation to a super-app this market has. Meta has been testing deeper commerce features like catalogues, integrated payments, and business tools. If WhatsApp successfully embeds shopping into its interface, millions of small sellers and kirana stores could access a ready-made distribution channel overnight. Combined with UPI, which already handles 55% of e-commerce payments, that could create genuinely low-friction commerce pathways.

Video commerce isn’t dead either. Globally, consumers who watch livestream shopping events are reportedly 70% more likely to purchase. That conversion potential exists in India too, once the connectivity infrastructure catches up to every corner of the nation.

The Honest Assessment

India didn’t get its Pinduoduo. What emerged instead was a network of micro-entrepreneurs selling affordable goods through personal WhatsApp networks, alongside cautious experiments by established players like Myntra and HUL.

The fact that the sector’s poster child Meesho continues losing thousands of crores annually while steadily pivoting toward a traditional marketplace model reveals just how challenging pure social commerce remains here. The trust deficit, infrastructure gaps, and economic constraints aren’t problems that clever product design or aggressive marketing can solve quickly.

Over the coming decade, social commerce will likely settle into a supporting role within India’s e-commerce ecosystem rather than transforming it. It may prove valuable for onboarding first-time online shoppers in smaller towns, for specific product categories where personal recommendations matter, and as an additional distribution channel for brands. But the revolution that investors once anticipated, where social platforms become primary shopping destinations, looks increasingly unlikely.

The ambition was never misplaced. The market conditions simply demanded a different playbook. One that’s still being written.

In other news, have you been checking out the crosswords below these articles? Try them out for yourselves, and see how quickly you can solve them!

Until shopping transforms again, ReadOn!

ReadOn Insights Crossword 21-01-2026

Hints:

Across:

1: The underlying social condition driving demand for a daily life-check app amid weak social bonds and urban isolation.

6: A growing market segment focused on products and services for the elderly population, driven by rapid ageing and family fragmentation.

8: The younger generation that built, adopted, and popularised the “Are You Dead?” app culture in China.

9: A Chinese phrase meaning “lying flat,” symbolising youth disengagement from traditional career, marriage, and consumption pressures.

10: Where the viral “Are You Dead?” app reflects a growing loneliness and social isolation crisis.

Down:

2: Elderly individuals are increasingly living without children in China due to low fertility rates and urban migration.

3: The social media platform where users discussed fears of dying alone without anyone noticing.

4: A Chinese mobile app that asks users every day if they are still alive, functioning as a personal “life-check” reminder.

5: A megacity often cited as representing urban isolation among young professionals.

7: The publication cited for China’s demographic trends, marriage decline, and social change data.

To solve this puzzle, click here!