Puma's Chinese Takeover

Nope, not Poma. Now even your authentic Pumas can be China ka maal!

At ReadOn, we don’t just report the markets. We help you understand what truly drives them, so your next decision isn’t just informed, it’s intelligent.

In January 2026, a Chinese company became the largest shareholder of Puma.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Puma, the brand born from one of business history’s most bitter family feuds. The company that put shoes on Pelé’s feet during the 1970 World Cup. The one that sponsored Usain Bolt when Nike and Adidas wouldn’t give him the time of day.

That Puma now has a Chinese sportswear giant as its biggest investor.

The buyer? Anta Sports. A company most people outside China have probably never heard of. And yet, Anta is already the world’s third-largest sportswear company by revenue. It’s actually bigger than Puma itself.

So how did we get here? How did a brand rooted in European athletic heritage end up anchored by a company that started making shoes in a small Chinese factory in 1991?

Let’s rewind.

Two Brothers, One Town, Eternal Rivalry

The Puma story begins in a laundry room in Bavaria, 1919.

Rudolf and Adolf Dassler started making sports shoes together in their mother’s washroom in Herzogenaurach. By 1936, their shoes were on Jesse Owens’s feet as he won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics.

But World War II tore the brothers apart. During an Allied bombing raid in 1943, Adolf reportedly muttered “Here are the bloody bastards again” as Rudolf’s family sat in the same shelter. Rudolf assumed the insult was directed at him. Post-war, Rudolf was briefly arrested — and believed Adolf had turned him in.

In 1948, the brothers formally split. Adolf took the main factory and founded Adidas. Rudolf crossed the river, took a third of the workers, and started what would become Puma.

Herzogenaurach became known as “the town of bent necks.” Locals would check strangers’ shoes before speaking to them. The brothers were buried at opposite ends of the town cemetery. They never reconciled.

Rudolf positioned Puma as the edgier, more rebellious sibling. Speed and style over institutional rigour. It worked… for a while.

The Rise, The Plateau, The Problem

Puma had its moments of glory.

In 1970, the company pulled off perhaps the greatest marketing stunt in sports history. Before Brazil’s World Cup quarter-final, Pelé walked to midfield and asked the referee for time to tie his shoelaces, while Puma’s cameramen zoomed in on his boots. Brazil won the tournament. Puma’s sales exploded.

In 2003, Puma signed a lanky 16-year-old Jamaican sprinter named Usain Bolt. Nike and Adidas had passed on him. Bolt became the fastest man in history and eventually got Puma’s first-ever lifetime deal for a track athlete.

But here’s the thing about Puma. It never quite broke through to the top tier.

Nike crushed everyone with marketing muscle. Adidas scaled through operational excellence and global systems. Puma? It cycled through revivals and slumps. Strong brand recall, inconsistent execution. Never collapsing, but never dominating either.

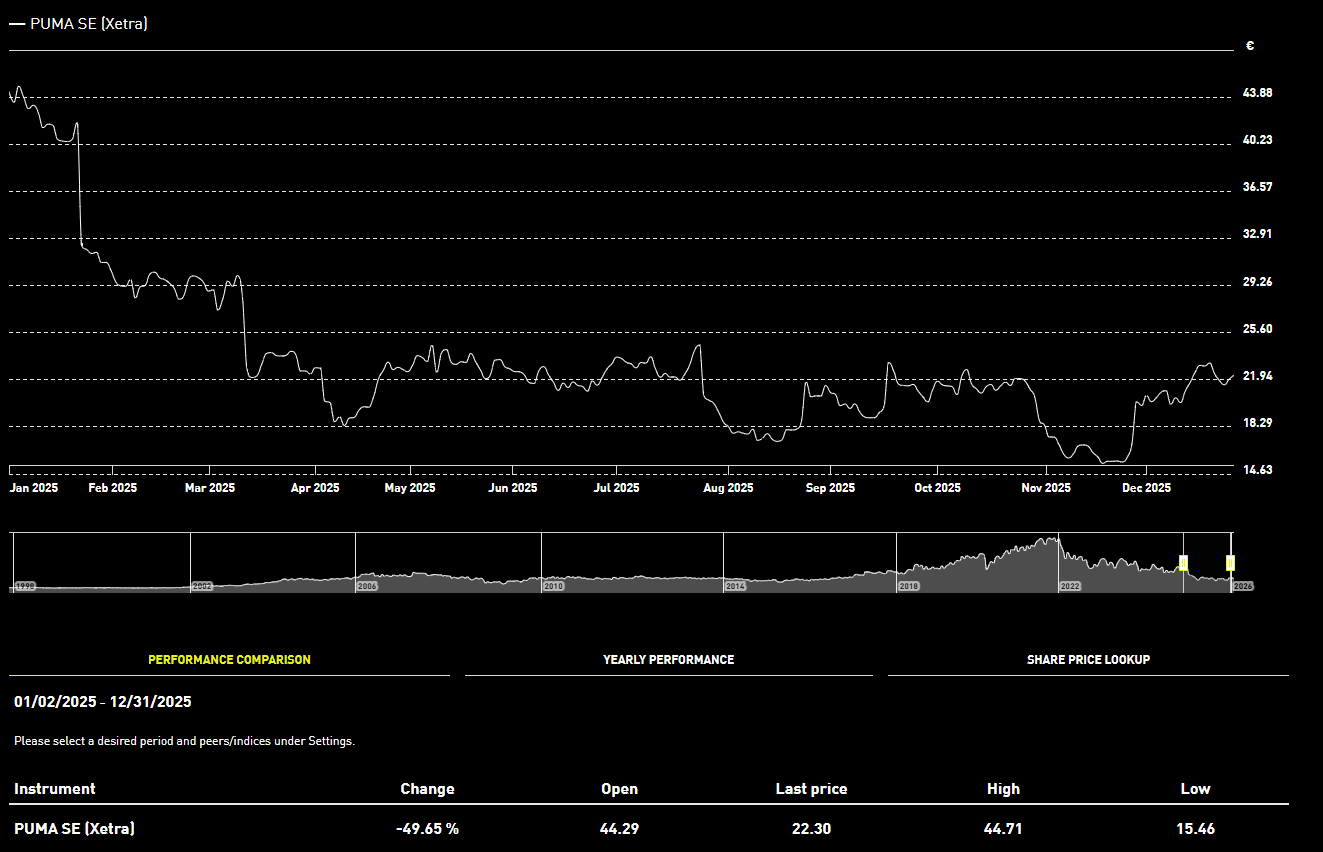

By 2025, the cracks were showing. Sales fell over 15% in the third quarter. The company posted a €62 million net loss. Its stock had crashed nearly 50% during the year.

The French luxury group Kering, which had once owned a controlling stake, had already spun off Puma in 2018 to focus on Gucci and Saint Laurent. The Pinault family’s holding company, Artémis, retained about 29% but called the stake “non-strategic.”

Puma needed a lifeline. Enter Anta.

From Factory Floor to Global Force

Anta’s origin story couldn’t be more different.

Inn1986, a 16-year-old named Ding Shizhong borrowed 10,000 yuan (about $1,500) from his father and bought 600 pairs of shoes to sell in northern China. Five years later, he and his brother pooled family savings to start Anta in Jinjiang, Fujian Province, a coastal region that would become China’s shoe-making capital.

Anta didn’t start with dreams of global domination. It was a contract manufacturer. An OEM supplier. The kind of company that makes products for other people’s brands.

But Ding spotted something Nike and Adidas missed. Hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers in tier-2, tier-3, and tier-4 cities who wanted aspirational sportswear but couldn’t afford Western prices.

So Anta built for them. Mass-market, affordable, but good enough to feel premium. And crucially, it built distribution like no one else. By 2007, Anta operated over 5,000 stores. By 2011, nearly 8,000. These weren’t fancy flagship outlets in Shanghai — they were stores in cities most Westerners have never heard of.

Anta went public in Hong Kong in 2007. And then it did something that would define the next two decades of its strategy.

It started buying.

The Acquisition Playbook

In 2009, Anta acquired the China trademark rights to Fila for about $46 million. At the time, Fila China was a disaster. Fifty stores. Losing money.

Anta proved them wrong.

It repositioned Fila as premium athleisure for urban, upper-middle-class consumers. It converted entirely to a direct-operated retail model. It invested heavily in celebrity endorsements. Store count went from 50 to 2,000. Average revenue per store more than doubled.

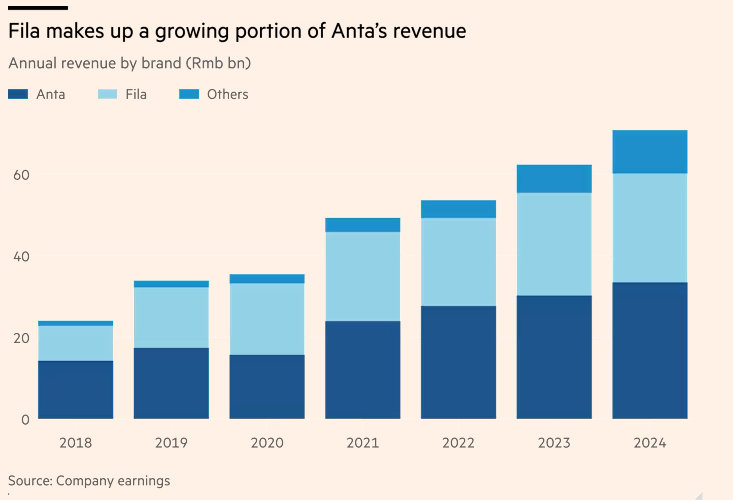

By 2021, Fila China’s revenue exceeded ¥20 billion. A brand bought for $48 million now contributes nearly 38% of Anta Group’s total revenue.

The lesson was clear. Western brands can thrive under Chinese operational management, if you preserve their identity and invest in local execution.

Emboldened, Anta went bigger. In 2019, it led a consortium to acquire Amer Sports, the Finnish company that owns Arc’teryx, Salomon, and Wilson for €4.6 billion.

Same playbook. Maintain brand autonomy. Invest in growth. Leverage China’s massive consumer market.

The results? Amer Sports revenue grew at a 20% compound annual rate from 2020 to 2022. China’s share of Amer revenues climbed from 8% to over 19%. In January 2024, Amer listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Anta had proven it could buy struggling Western brands and make them shine.

The Puma Play

Which brings us back to January 2026.

Anta announced it would pay €35 per share (a 62% premium to Puma’s previous closing price) to acquire Artémis’s entire 29.06% stake. The total deal value is about $1.78 billion, funded entirely from Anta’s cash reserves of ¥52 billion.

Why 29.06% and not 30%? Because 30% would trigger mandatory takeover rules under German law. Anta wanted influence, not control.

Puma’s shares surged 20% on the news. Analysts called it validation of Puma’s turnaround potential and Anta’s operational credibility.

The strategic logic is compelling.

Puma derives only 7% of its revenue from China. Anta commands 23% market share there; more than Nike (20.7%) and far more than Adidas (8.7%). Anta’s distribution infrastructure in China is unmatched. If anyone can unlock Puma’s China potential, it’s Anta.

Meanwhile, Puma’s strength in Europe, Latin America, and football gives Anta something it’s been missing. A globally recognised lifestyle brand with World Cup exposure.

Anta’s Global VP said it plainly: “Puma has more potential in the Chinese market where they are underrepresented. We have a lot of insight on how to make Puma more successful in China.”

What This Really Means

Let’s zoom out and look at the bigger picture.

The global sportswear industry is shifting. Nike lost 53% of its stock value over the last five years. Its innovation pipeline dried up while it over-relied on retro designs. Adidas has been recovering but remains cautious. Challenger brands are growing faster than incumbents.

McKinsey estimates that fast-growing challengers will capture 57% (nearly triple their 2020 share) of the sportswear segment’s economic profit.

And leading that charge is a Chinese company that most Western consumers still can’t name.

The Anta-Puma deal is a signal that the rules of the game are changing. Brand heritage matters less when you don’t have the distribution muscle to reach 1.4 billion Chinese consumers. Marketing flair means little if your supply chain can’t deliver products in six months instead of eighteen.

The West built the brands. The East is learning to run them better.

The Unanswered Questions

Of course, this isn’t a done deal in the strategic sense.

Can Anta replicate its Fila success with a minority stake in a publicly traded German company? Will Puma’s management accept “suggestions” from its new largest shareholder? Can heritage and efficiency coexist when the cultures are so different?

The Geely-Volvo acquisition offers hope. When Geely bought Volvo from Ford in 2010, sceptics predicted disaster. Instead, Geely gave Volvo autonomy, invested heavily, and watched the Swedish carmaker post record sales.

Anta has signalled it will follow the same playbook. Investment plus autonomy. Influence without control.

But sportswear isn’t cars. Brand perception is everything. And Puma’s identity has always been about being the scrappy underdog, not the subsidiary of a Chinese conglomerate.

The Bottom Line

Rudolf Dassler probably never imagined this.

The company he founded out of spite, in a bitter split from his brother, sponsored by the greatest athletes of multiple generations, now has its future partly written in Mandarin.

But that’s how global business works. Brands don’t disappear. They get adopted by whoever understands the next consumer best.

Right now, that’s Anta.

In other news, have you been checking out the crosswords below these articles? Try them out for yourselves, and see how quickly you can solve them!

Until shoes change hands again, ReadOn!

ReadOn Insights Crossword 02-02-2026

Hints:

Across:

3: The political figure at the centre of some of the largest and most liquid prediction-market bets.

5: The economist who explained how prices act as mechanisms to aggregate dispersed information.

7: The core regulatory criticism of prediction markets, based on concerns that they resemble betting rather than information discovery.

8: The owner of the New York Stock Exchange, which invested $2 billion in Polymarket.

10: A blockchain-based platform hosting bets on elections, geopolitics, and real-world events.

Down:

1: A trader who reportedly earned over $80 million by betting on US elections.

2: A US-based prediction market operating under regulatory oversight as a derivatives exchange.

4: An Indian prediction platform that shut down following the gaming and betting ban.

6: The country that banned prediction markets in August 2025.

9: The US regulator that oversees prediction markets as financial derivatives.

To solve this puzzle, click here!

30.01.2026 (Answer Key)

Across:

2: Finfluencers

4: GenZ

7: China

8: Dormancy

9: SEBI

Down:

1: Demat

3: Literacy

4: Gold

5: Trust

6: India

Excellent breakdown. The Fila turnaround story is the real proof of concept here, going from 50 stores to 2000 while becoming 38% of Anta's revenue. What makes this diffrent from typical PE rollups is Anta isn't strip-mining value, they're actually building distribution infrastructure that Western brands cant replicate on their own in China. The 29.06% stake avoiding mandatory takeover rules is clever too, gives influence without triggering regulatory scrutiny.