India's Wind Problem Isn't the Wind

The winds are fast, but the system's slow.

At ReadOn, we don’t just report the markets. We help you understand what truly drives them, so your next decision isn’t just informed, it’s intelligent.

50 GW.

That’s roughly how much renewable energy capacity is sitting idle across India right now. Not because the turbines are broken. Not because the wind isn’t blowing. But because there simply aren’t enough power lines to carry the electricity.

Think about that for a moment. We have projects ready to deliver clean energy. We have willing buyers. But the highways to move this power? They’re either jammed or incomplete. In Rajasthan alone, about 8 GW of renewable projects are waiting on transmission lines, and during peak wind-solar periods, many generators are told to simply switch off because the grid can’t absorb what they’re producing.

The Potential is Staggering

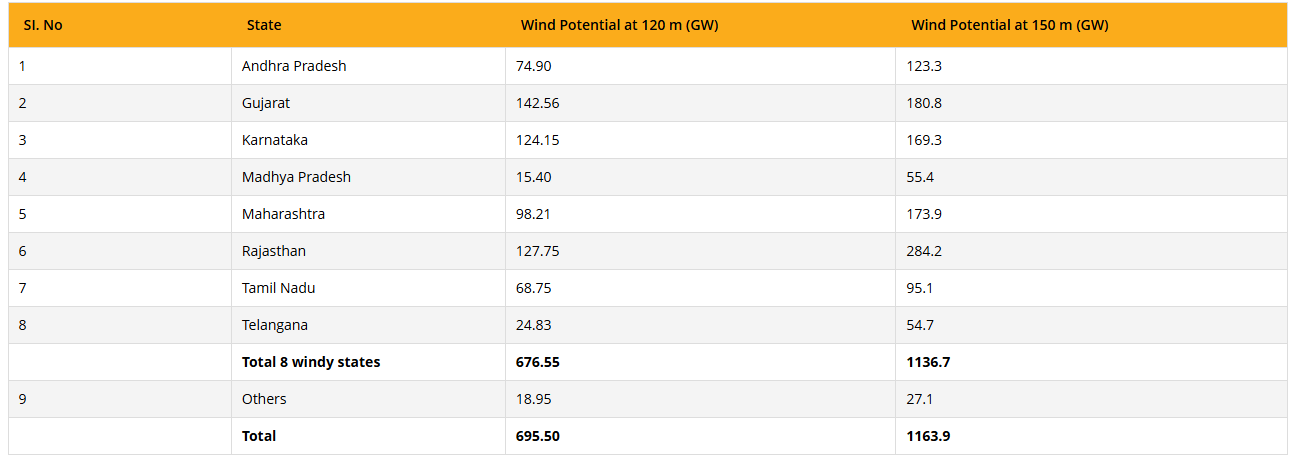

India ranks fourth globally in wind energy installations with over 50 GW of capacity. Wind farms dot Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. The government’s own resource maps show an estimated 695 GW of onshore wind potential at 120-metre hub heights. At 150 metres, that number jumps to over 1,160 GW. Most of this resource lies concentrated in just eight windy states.

Wind is particularly valuable for a reason. Turbines generate at night and during monsoon months, naturally complementing daytime solar generation. This round-the-clock capability is why officials call wind energy the backbone of affordable clean power. Round-the-clock clean power schemes rely on combining wind with solar and batteries, since wind often blows when the sun isn’t shining.

India also has a strong domestic wind industry capable of manufacturing 18 GW of turbines annually. Over 17 manufacturers operate here, including global players and homegrown firms like Suzlon. We’re the world’s third-largest wind turbine manufacturing hub. This manufacturing base doesn’t just serve Indian projects. It exports to global markets. Nurturing wind power means boosting high-tech manufacturing and thousands of skilled jobs.

The ingredients for success are all there. Strong winds, proven technology, industrial capability, and clear strategic value.

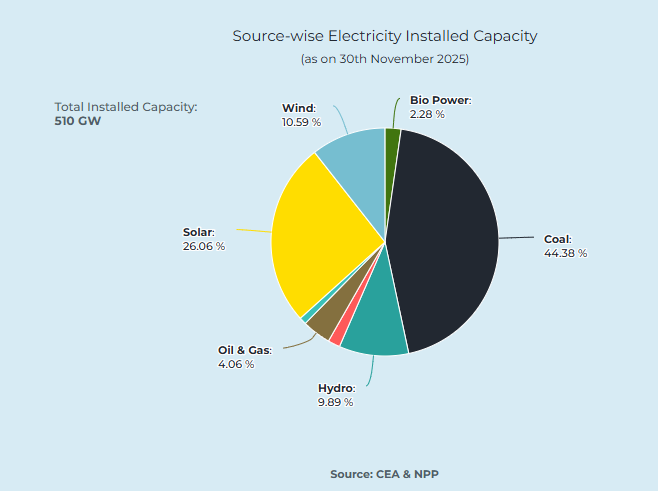

So why has wind contributed just 10% of India’s total installed power capacity while solar, virtually nonexistent a decade ago, surged past 60-70 GW?

The Five Bottlenecks

Land is the first hurdle. A 100 MW wind farm can span tens of square kilometres, often across private farmlands or village commons. Fragmented ownership means developers must negotiate with dozens of stakeholders just to piece together a viable site. Multiple state departments like revenue, forests, local panchayats have to sign off on acquisition and land-use changes. These multi-layered approvals drag on for months, sometimes years. In many windy areas, especially in Gujarat and Rajasthan, suitable sites are also in ecologically sensitive zones or community grazing lands, triggering additional clearances and local anxieties.

And it’s not just bureaucracy. Local communities often fear loss of livelihood when common pasture or fertile fields are taken. Some early wind projects did a poor job of engagement, leading to mistrust that persists today. In states like Maharashtra and Karnataka, protests and court cases have halted projects entirely. The human side of renewables cannot be ignored.

Even when private land is sorted, right-of-way for transmission lines can pose another hurdle. In Rajasthan, a court order to protect the endangered Great Indian Bustard forced new transmission lines to be built underground or rerouted, delaying a major wind power evacuation line.

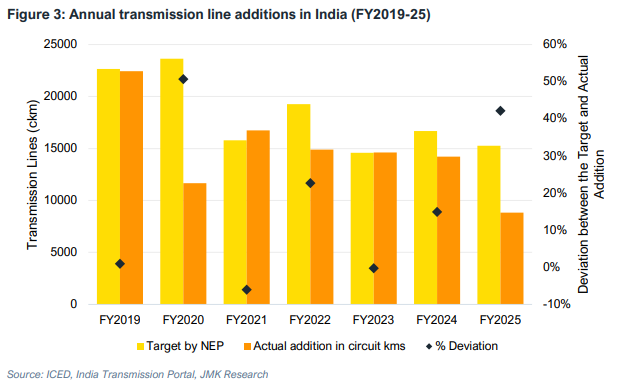

Grid connectivity is the second chokepoint. In FY2024-25, only around 8,830 circuit-kilometres of new transmission lines were commissioned against a target of 15,253. That’s a 42% shortfall, the lowest interstate transmission addition in a decade. The causes range from financing issues to right-of-way disputes to contractor delays.

Meanwhile, some developers gamed the system by grabbing grid connectivity for projects they never built, effectively blocking others from using limited capacity. By late 2025, the grid operator finally cracked down, cancelling 6.3 GW of such connectivity approvals from 24 projects that failed to meet commissioning deadlines. Many developers are now fighting these revocations in court, blaming the transmission lines that were promised but never materialised.

Grid congestion also causes curtailment, or instructions to back down generation because the network can’t carry it. It’s a bitter pill for a renewable developer to curtail free fuel while fossil plants elsewhere keep running.

Then there’s the policy whiplash. In 2017, the government shifted from feed-in tariffs to competitive auctions. Initial bids crashed to around ₹2.5 per kWh, which looked great on paper. But aggressive bidding led to projects that couldn’t achieve financial closure. By 2019, more than half of awarded wind projects from early auctions were delayed. From 2018 through 2020, annual installations barely crossed 1.5 GW a year. The sector actually shrank year-on-year in 2017.

Recent course corrections have stabilised tariffs around ₹3.6-4.0 per kWh, which are considered sustainable given rising interest rates and commodity costs. But there’s a kicker. 45 GW of renewable capacity completed bidding and even got grid connectivity. Yet, it didn’t have signed power purchase agreements as of late 2025.

Why? Many state distribution companies are cash-strapped, collectively carrying lakh crores of debt. They’re dragging their feet, expecting prices to fall further or preferring cheaper short-term market power. Between 2020 and 2024, about 19% of all issued renewable tenders (a staggering 38.3 GW) were eventually cancelled for various reasons, including poor PPA uptake.

Repowering presents its own complications. India has thousands of old turbines from the 1990s and 2000s, many below 500 kW capacity, sitting on prime wind sites. Upgrading them to modern 2-3 MW machines could double or triple output from the same land. The potential is around 25 GW.

But there’s a catch. Many legacy wind farms have highly fragmented ownership. In Tamil Nadu, the early wind boom attracted factory owners and high-net-worth individuals who each bought one or two turbines for tax benefits. A single wind farm might have 30 different owners. Getting all of them to agree on shutting down existing turbines and pooling plots for repowering? Nearly impossible. Not a single major wind farm has been fully repowered in India yet.

Finally, offshore wind remains a distant dream. The government announced a 37 GW trajectory by 2030 and planned specific tenders. But by mid-2025, the initial 4,000 MW seabed lease offer and 500 MW Gujarat project were cancelled due to weak global interest. Offshore wind requires massive upfront investment, specialised equipment, and a supply chain that simply doesn’t exist in India yet.

The Task Force Response

The government has acknowledged the problem. A dedicated Wind Power Task Force, bringing together central agencies, state utilities, industry bodies, and technical experts. Its mandate is to examine land acquisition woes, right-of-way issues, transmission delays, tariff structures, and construction timelines.

The Task Force is also looking at benefit-sharing models to improve community acceptance and reviewing grid connectivity procedures. The idea is simple. Get everyone to the same table instead of letting agencies operate in silos.

FY2024-25 brought 4.1 GW, the highest in a single year since the mid-2010s. Cumulative capacity crossed 50 GW by mid-2025.

But here’s the math that matters. Hitting 100 GW by 2030 requires adding around 10 GW each year. That’s more than double the current rate. Even optimistic forecasts suggest India might only reach 75 GW by 2030 under business-as-usual conditions.

What to Watch

The hybrid model could be the breakthrough. A significant portion of new wind capacity is now coming through combined wind-solar auctions or round-the-clock power tenders. This smooths output and makes power more attractive to discoms. Large hybrid parks in Gujarat’s Kutch, some planned for 30 GW, could be game-changers if executed.

The General Network Access regime, if implemented properly, could also help. Generators would simply feed into the grid without pre-committing to specific buyers. This removes a major source of complexity.

And if the Task Force can unlock even a few gigawatts stuck in the pipeline within a year, it would earn credibility and demonstrate that coordination, not just targets, is finally being taken seriously.

The Bottom Line

India’s wind sector isn’t failing because of technology or resources. It’s failing because of coordination failures, bureaucratic tangles, and misaligned incentives across a fragmented system. The wind blows freely, but navigating India’s regulatory and infrastructure maze does not come free.

The next five years will determine whether India rides this wind to its climate goals or remains, as it stands today, a great wind power story still waiting to be written. The turbines are ready. The question is whether everything else can catch up.

In other news, have you been checking out the crosswords below these articles? Try them out for yourselves, and see how quickly you can solve them!

Until next time, ReadOn!

ReadOn Insights Crossword 22-01-2026

Hints:

Across:

2: The country linked to the 2025 cyber breach of a Norwegian hydroelectric dam.

4: The Indonesian president whose likeness was impersonated in deepfake scam videos.

6: The core organisational capability—combining preparedness, response, and recovery—that determines whether firms can survive major cyberattacks.

9: Britain’s largest carmaker, forced into a five-week production shutdown in 2025 following a major cyberattack.

10: The most common form of cyber-enabled fraud affecting individuals globally in 2025, often involving deceptive emails, messages, or links.

Down:

1: Artificial Intelligence, identified by 94% of executives as the biggest driver of change in the cybersecurity threat landscape.

3: Business networks where a single weak vendor or software supplier can trigger cascading cyber failures across multiple organisations.

5: AI-generated video and audio content used to impersonate leaders, executives, or relatives to commit fraud and misinformation campaigns.

7: The organisation that released the Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2026.

8: A cyber threat that has overtaken ransomware as the primary concern of CEOs, due to its scale, speed, and reputational damage.