India's Import Export Overlap

If India has a shortage of oil, and we import it, then why is oil also one of our biggest exports?

At ReadOn, we don’t just report the markets. We help you understand what truly drives them, so your next decision isn’t just informed, it’s intelligent.

Every year, India spends over ₹18 lakh crore importing mineral fuels and their derivatives, like crude oil and petroleum products. It’s our largest import bill, that’s roughly 3% of our GDP. Yet the same year, we exported ₹7.25 lakh crore worth of the exact same commodity group.

At first glance, this looks absurd. If we’re so desperate for energy that we’re running up massive import bills, why are we simultaneously shipping it out? Wouldn’t it make more sense to keep every drop for domestic use and cut our trade deficit by exactly that amount?

Mineral fuels aren’t alone. According to a study by MVIRDC World Trade Center Mumbai, there are 65 products across nine sectors where India is both a major importer and exporter. Like gems and jewellery, electrical machinery, mechanical equipment, organic chemicals. The pattern repeats itself. We buy them, we sell them, often in staggering quantities.

We have read that countries export what they produce efficiently and import what they don’t. That’s comparative advantage. And it makes sense. Produce what you’re efficient at, trade for the rest. Everyone benefits. But that framework is too simplistic to capture what actually happens in modern trade. The overlap between India’s import and export lists is a feature of how global value chains actually work.

So why is there an overlap between export and import commodities?

Before answering that question, let’s get some basics clear and understand how trade shapes an economy.

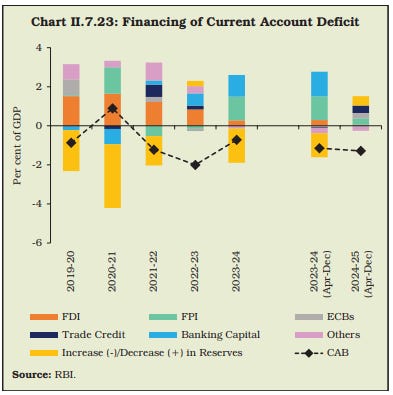

Starting with the Balance of Payments equation: Current Account + Capital Account + Change in FX Reserves = 0. It means every rupee India spends on imports has to come back somehow, through export earnings, money sent home by Indians working abroad, foreign investment, or by dipping into the RBI’s forex reserves.

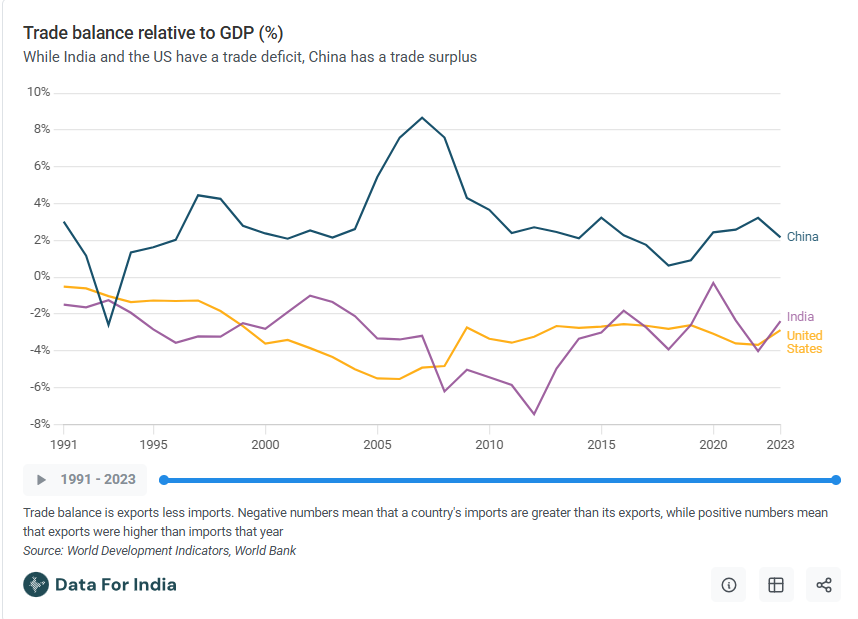

Generally, India has run a trade deficit of 2-6% of GDP for decades.

In FY25, our current account deficit was $23.3 billion i.e. a 0.6% of our GDP. More money left than came in. The capital account, mostly foreign investment, brought in $21.7 billion. That still left a $1.6 billion gap, which came from RBI’s forex reserves. When reserves drop, it signals we’re consuming more than we’re earning globally.

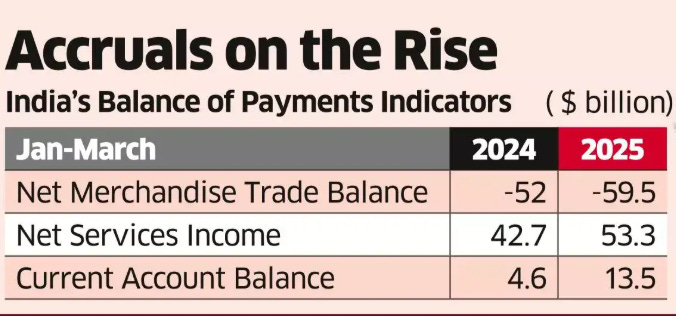

The deficit is driven almost entirely by merchandise trade. In FY25, India’s negative net merchandise balance was $59.5 billion. And the single largest contributor? Coal and petroleum crude, accounting for over 30% of all imports by value.

When a country runs a trade surplus, foreign buyers need its currency to purchase its goods, so demand for that currency rises and it appreciates. A trade deficit works in reverse: if a country consistently imports more than it exports, it needs more foreign currency—usually the US dollar, to pay for those imports. This pushes up the demand for USD and, by extension, puts downward pressure on the domestic currency.

In India’s case, this effect is magnified because a large part of the deficit comes from crude oil, which is almost entirely invoiced in USD. Every spike in crude imports, whether due to higher prices or higher volumes, translates into a spike in dollar demand. Over time, this persistent structural demand for USD contributes to the gradual depreciation of the rupee, alongside other factors like capital flows, inflation differentials, and global risk sentiment.

A weaker rupee makes imports more expensive in rupee terms, because Indian buyers must now spend more rupees to buy the same dollar-priced goods. Exports do become more competitive on paper, since Indian goods become cheaper in foreign currency terms, but the advantage is often diluted by import duties in partner markets, long-term contracts priced in dollars, or the fact that many of India’s export sectors rely heavily on imported inputs (like crude for refineries or chips for electronics). A weak rupee raises their input costs too, so the net benefit is not as large as textbooks suggest.

When imports become costlier due to a weaker rupee, the trade deficit can widen further, especially if those imports are inelastic essentials like crude oil, fertilizers, capital machinery, gold, or electronic components.

Now that the basic mechanics are out of the way, we can finally address the part that looks most counter-intuitive: why the very same categories that create India’s trade deficit are also the ones that reduce it.

The Value Chain Answer

Now back to the paradox. What India imports under “mineral fuels” isn’t what it exports. The category looks identical in trade statistics, but the products sit at entirely different stages of the value chain.

India imports crude oil (HS code 2709). We consume 265.7 million metric tonnes annually but produce only 28.7 MMTPA domestically. That’s 89% import dependence. We have oil reserves of around 651.8 million metric tons, but production lags due to aging wells, lack of new discoveries, and technology constraints. So we buy raw crude from the Middle East, Russia, and Latin America.

But what we export is refined petroleum products (HS code 2710). India has built massive surplus refining capacity. Reliance’s Jamnagar facility is one of the world’s largest. India’s total refining capacity stands at around 256.8 MMTPA whereas our domestic consumption of petroleum products stands at 233.3 MMTPA.

Refineries like Reliance, Nayara Energy, and IOCL operate near full capacity, importing crude, converting it into diesel, petrol, jet fuel, and petrochemicals, then exporting the finished products to the Netherlands, UAE, USA, and Singapore. India turns a low-value raw material into higher-value finished goods and captures the margin in between. The trade data lumps both crude imports and refined exports under “mineral fuels,” making it look contradictory when it’s actually two different products in two different markets.

This pattern repeats across sectors. India imports rough diamonds from the US, Singapore, Hong Kong, and UAE. What’s exported is cut and polished stones primarily to Hong Kong, the US, Japan, and Bahrain. India has a deficit in raw stones but handles 90% of the world’s polished diamond production.

Machinery and electronics follow the same logic. India imports high-precision equipment and semiconductors from Taiwan, Germany, and China but exports medium-tech machinery, smartphones, and engineering electronics where it has cost advantages and assembly capabilities. For iPhones assembled in India, approximately 20% of the value is “made in India” through labor, assembly, and some local components. The remaining 80% consists of imported parts. But the finished phone gets exported, and both the component imports and the phone exports show up under electrical machinery.

Under the same broad trade category, India operates at multiple levels. For some products, we’re raw material buyers. For others, we’re processing hubs. And for some, we’re assembly and export platforms. The trade data flattens these distinctions into a single line item, creating the illusion of contradiction.

But sometimes the overlap isn’t only about different sub-products within a category; India often continues to export even when the domestic market is tight and this brings us to a second layer of the story.

Contracts, Credibility, and Strategic Relationships

What trade statistics fail to capture is reliability. Exporters don’t operate purely on spot markets. They run on multi-year supply agreements, predictable shipment schedules, and long-term buyer relationships. Abruptly stopping shipments, even during domestic shortages, damages India’s credibility in global markets. And that credibility, once lost, rarely returns.

Consider what happened with onions in December 2023. India imposed an abrupt export ban due to domestic prices hitting ₹4,500 per 100 kg. The government later lifted the ban following farmer resentment, but by then, importing countries had already built up inventories elsewhere. According to shipping lines, container bookings were 60% lower than pre-ban levels. Buyers had moved on. The short-term domestic relief came at the cost of long-term export market share.

Similarly, petroleum products flow consistently to the Netherlands, Singapore, UAE, Australia, and Israel regardless of domestic fuel tightness. These buyers sign annual or multi-year contracts with Indian refiners. Even during the 2008 crude price spike, the 2013 rupee crisis, and the 2022 global fuel crunch, India didn’t abruptly shut refinery exports.

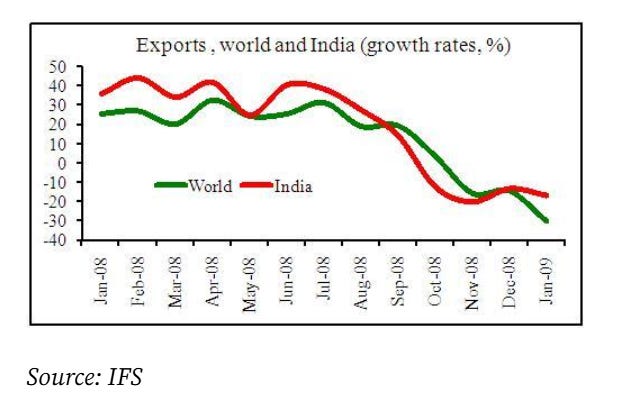

Exports do decline during these periods, but largely because global demand weakens, not because India pulls back supply.

There’s also a geopolitical dimension. India sometimes exports even during tight domestic conditions to maintain strategic relationships. Refined fuels flow to Israel, South Africa, and partners in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. These help India build and maintain diplomatic influence.

The power sector offers an even more recent example. India is the world’s third-largest electricity producer with an installed capacity of ~ 500 GW as of November 2025 and stands as a net power exporter. Yet millions across the country endure regular power outages. While projections suggest shortages may persist until 2027, India continues to supply substantial electricity to Bangladesh, Nepal, and Myanmar under long-term agreements and regional energy cooperation frameworks.

In February 2025, India’s electricity production reached 1,21,073 GWh, whereas consumption stood at 1,31,540 GWh. Despite domestic shortages, India exported electrical energy worth $1.49 billion in 2024-25, totaling over 21,500 GWh. Bangladesh alone accounted for $1.42 billion. Why export when domestic supply remains tight? For India, it’s not the generation capacity that causes the shortage, it’s the distribution. Electricity reaches our homes through discoms who buy it from generators and deliver it to us.

These DISCOMs often sign Power Purchase Agreements where they commit to selling a certain amount of power to a buyer, even foreign countries.

India cannot just reroute this electricity domestically during shortages.

These export commitments are made on a very long term basis of 25-30 years based on long-term bilateral agreements and regional energy cooperation deals. Breaking them would undermine India’s position as a reliable energy partner in South Asia.

The Time Lag Problem

Finally, there’s the issue of timing. The 3Ps- Production, Procurement, and Policy all involve time lags, which can create situations where exports and domestic shortages overlap.

A decision to export may be based on an earlier harvest or stock estimate. By the time a domestic shortage becomes visible in retail markets, export flows and contracts are already in motion. Similarly, export bans or duties are often reactive. Meaning that they come after significant quantities have already left, creating the perception that “we’re short but still exporting” even though policy has started tightening.

This isn’t incompetence. It’s the inherent difficulty of matching real-time domestic needs with forward-looking export commitments. Markets move faster than policy. And once goods are in transit or contracts are signed, reversing them imposes costs that often outweigh the short-term relief of keeping supplies domestic.

What It All Means

Understanding the overlap between India’s import and export doesn’t make the trade deficit go away. But it does clarify why simplistic solutions like “just stop exporting what we import” miss the point entirely. The question isn’t whether we should export or import. It’s how we move up the value chain, build capabilities in higher-margin products, maintain reliability in global markets, and navigate the inevitable tensions between domestic needs and export commitments. That’s the real trade-off. And it’s far more complex than any textbook would suggest.