Beyond the Silver Shortage

Let's take a look at some second order impact of the metal's shortage.

At ReadOn, we don’t just report the markets. We help you understand what truly drives them, so your next decision isn’t just informed, it’s intelligent.

Guess which asset class outperformed most major asset classes this year?

You probably know the answer. Silver.

In 2025, silver surged about 138%, making it the best-performing major asset of the year. Gold wasn’t far behind, rising 74.5%, its strongest annual gain in decades. Whereas, the Nifty 50 delivered a return of roughly 10% as of 19 December 2025.

Silver crossed $70 an ounce in late 2025, touching levels not seen since 2012.

The metal that powers solar panels, enables AI computing, and ensures electric vehicles don’t catch fire has become expensive, and scarce.

This isn’t another piece about why silver prices are rising. That story is well known. What matters now is the second-order effect. What happens to industries that depend on silver as a core input?

Industry accounts for roughly 50–60% of global silver consumption.

For manufacturers, silver is not a hedge or a store of value. It’s a cost line. And when that line starts ballooning, behaviour changes. As Peter Drucker famously put it, “what gets measured gets managed”. Rising input prices force companies to re-measure everything like design choices, material intensity, sourcing strategies, even end products.

If this sounds familiar, it should.

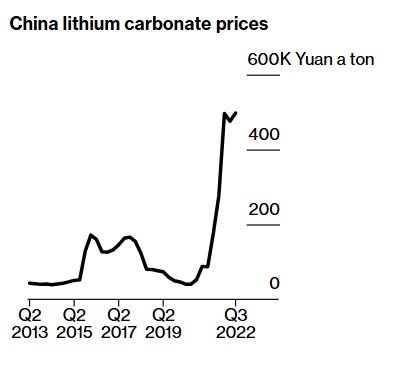

Lithium offers a recent precedent. In 2021, lithium carbonate traded near $36,514 per tonne. By early 2022, prices surged past $50,000 as EV demand exploded and supply lagged. Later that year, lithium went past $70,000 per tonne. Bloomberg estimated that the spot value of global lithium consumption jumped from $3 billion in 2020 to $35 billion in 2022.

The narrative was clear. This was a case of structural scarcity.

Then the market flipped.

By late 2023, lithium prices had collapsed nearly 80%, falling back to $13,000–14,000 per tonne. Today, they trade only marginally above 2021 levels. The rally didn’t break because demand vanished overnight. It broke because industry adapted. New supply came online at speed. Battery chemistry shifted toward lithium-light LFP cells. Sodium-ion batteries entered mass production. Subsidies were withdrawn. Prices did what prices eventually do when incentives change.

That same question now hangs over silver.

When a critical input becomes too expensive, do industries absorb the cost, pass it on, or engineer their way around it? And if they do, what does that mean for silver’s rally?

Let’s find out!

The Arithmetic of Scarcity

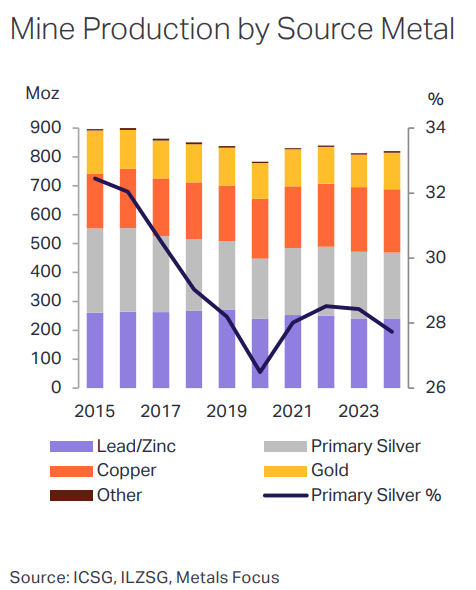

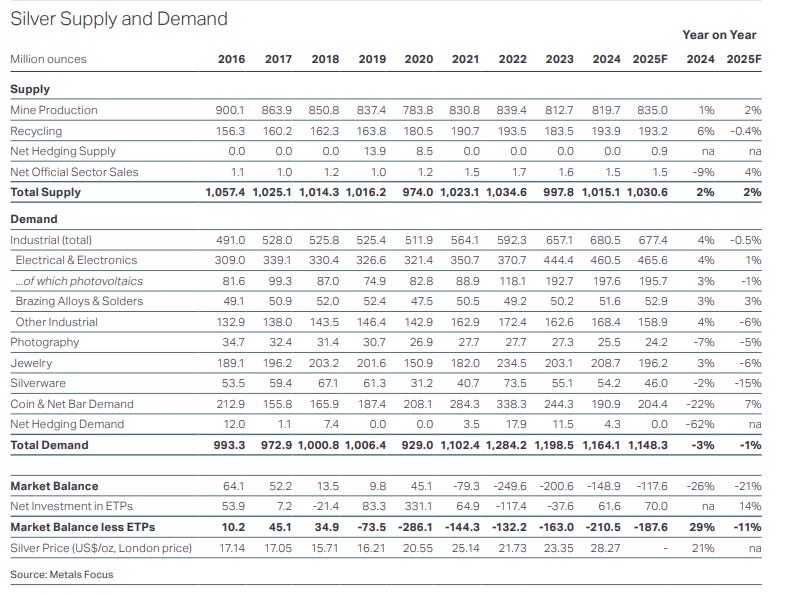

The silver market’s troubles begin underground. Mine production grew just 0.9% in 2024 to 819.7 million ounces, despite prices jumping 21% that year. The reason is simple physics. 72% of silver comes as a byproduct of copper, lead, and zinc mining.

You can’t just “produce more silver” without ramping up base metal operations, which have their own demand cycles and economics. Unlike lithium, where brine operations expanded in 18-36 months, silver mines take 5-8 years from discovery to production.

Ore grades have declined ~30% over the past decade. Recycling, while reaching a 12-year high of 193.9 million ounces in 2024, adds only about 16% to total supply, far less flexible than lithium’s quickly-scalable refining capacity.

Against this constrained supply, total silver demand reached 1.16 billion ounces in 2024. The deficit? 148.9 million ounces. That’s the fourth consecutive year of shortfalls, with cumulative deficits from 2021-2024 totaling 678 million ounces. That’s equivalent to ten months of global mine production. Add 2025’s projected 95-117 million ounce gap, and you’re looking at 820 million ounces of deficit over five years.

By now, you’d mostly be aware of the uses of silver. Solar panels, electronics, electric vehicles, medical devices, so we won’t get into the intricacies of each application.

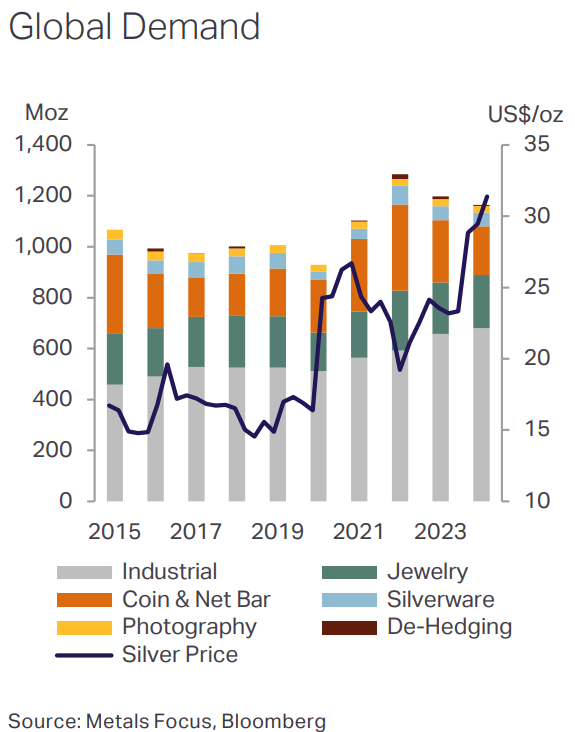

What matters is the demand pattern. Industrial demand hit a record 680.5 million ounces in 2024, representing 59% of total consumption. Silver is transforming from primarily a precious metal into an industrial commodity.

The driver? Three mega-trends colliding simultaneously.

AI infrastructure (data center power demand up 5,252% since 2000), electric vehicle transition (EVs using 67-79% more silver than combustion engines), and renewable energy buildout (solar consumption tripling from 54 million ounces in 2014 to 197.6 million in 2024). They’re all accelerating at once.

Meanwhile, traditional demand is weakening. Jewelry fell 3% in 2024 and faces a 6% decline in 2025. Silverware dropped 2% and is forecast down 11% this year. Physical bar and coin investment has been declining for three consecutive years. The deficit is structural. Supply grows less than 1% annually while industrial consumption surges 4-7% year-over-year.

Which brings us to the critical question: What are industries actually doing about it?

Where the Pain Is Hitting Hardest

When silver hit $50 an ounce, certain industries were hurt more than others. For solar panel manufacturers operating on razor-thin margins of 5-15%, silver suddenly represented a meaningful cost pressure. Calculate it: at 20 grams per panel and $50 per ounce, that’s $32 worth of silver per panel—5-8% of the total manufacturing cost for panels selling at $400-500 each.

Electronics manufacturers felt it differently. With 1.24 billion smartphones produced annually, each containing 200-300mg of silver, the aggregate cost jumped from roughly $280 million at $25/oz to $560 million at $50/oz. For semiconductor fabs processing billions of chips, silver waste streams that were ignored at $20/oz suddenly represented hundreds of millions in lost material.

Even automotive suppliers took notice. At 25-50 grams per EV and 20 million EVs projected for 2025, that’s 16-32 million ounces annually. That’s worth $800 million to $1.6 billion at $50/oz. For an industry where suppliers negotiate costs down to the tenth of a cent, a doubling in silver prices demanded a response.

The Three-Pronged Response: Progress and Limitations

Industries are responding with three ongoing strategies. They are reducing silver content per unit (thrifting), substituting alternative materials, and recovering silver through recycling. Early results show both remarkable achievements and stubborn limitations.

Thrifting efforts are showing measurable impact. Solar manufacturers are actively reducing silver loading, achieving 15-20% reductions in 2024 alone. The techniques continue evolving.

France’s CEA research institute recently achieved below 14 milligrams per watt using copper ribbons combined with copper-silver pastes. That’s a 44% reduction from the industry average of 20-25 mg/W just two years ago. Scale this across global production: at 444 GW annual capacity, reducing from 25 mg/W to 14 mg/W saves 4.88 million ounces annually, worth $244 million.

The early results look good. 2025 marks the first-ever forecast decline in solar silver demand, down 5% to 185 million ounces despite record panel installations. Without ongoing thrifting efforts, demand would have hit 230-240 million ounces. The industry is on track to save 45-55 million ounces worth $2.25-2.75 billion through optimization efforts, though this remains a moving target as installations continue accelerating.

Material substitution is advancing but faces a long road ahead. AIKO, a Chinese manufacturer, started producing copper-metallized solar modules in January 2025 and is scaling toward 10 gigawatts by year-end. At 5-7 grams of silver saved per panel, that’s 1.6-2.25 million ounces potentially saved annually once at full scale, worth $80-112 million in material costs.

Jiangsu Xianghuan Technology (JXTC) is progressing from a 300-megawatt pilot line to equipment orders for 1-gigawatt production.

In electronics, Intel and TSMC are deploying closed-loop recycling systems to reclaim silver from manufacturing waste. Global semiconductor packaging consumes 1,200-1,500 tonnes of silver annually (37-47 million ounces).

Advanced packaging techniques are being introduced to reduce silver usage per chip while improving performance. Through-silicon vias, chiplet architectures, and 2.5D/3D packaging are gradually being adopted.

These ideas are still nascent though, and widespread implementation across the industry will take several more years.

If fully realized, the optimization impact by 2027-2028 could be significant. Solar thrifting potentially saves 45-55 million ounces and electronics recycling could add 8-10 million ounces. Combined, roughly 60 million ounces of demand reduction or supply addition. But these are targets, not guarantees.

The Execution Barriers: Why Progress Is Slow

Three fundamental challenges are limiting how fast these solutions can scale, and they explain why optimization efforts cannot quickly resolve the supply-demand imbalance, despite real progress.

First: Innovation timelines that resist compression. Copper plating for solar panels took over a decade to develop. Suntech began exploring it in the early 2000s. JXTC’s founders worked on it for ten-plus years. Commercial viability only arrived in 2023-2024.

Now comes the scale-up phase. 2025-2027 for gigawatt-scale production, 2027-2030 for industry-wide adoption. If copper metallization captures 10% market share by 2027, 30% by 2028, and 50% by 2030, the silver savings would be 34.5 million ounces in 2027, 121 million in 2028, and 260 million by 2030.

That 260 million ounce reduction would nearly eliminate solar’s current demand footprint. But it assumes 50% adoption by 2030. That’s aggressive for an industry where capital equipment has 10-15 year lifespans and most factories were built for silver screen-printing. If adoption lags to 30% by 2030 instead, you lose 80 million ounces of expected savings. The equipment is expensive, the learning curve is steep, and the risk is real.

Second: Technology transitions that increase silver intensity even as optimization continues. The solar industry is simultaneously shifting to next-generation TOPCon and HJT cell architectures. These are more efficient, as they convert 24-26% of sunlight to electricity versus 22-23% for older PERC cells. But they use ~120 milligrams of silver per watt versus 100 mg/W for PERC. That’s a 50% increase.

The German Mechanical Engineering Industry Association data shows TOPCon overtook PERC as the dominant architecture in 2024. So even as manufacturers thrift aggressively, the technology transition pulls in the opposite direction. This creates a frustrating dynamic. Optimization reduces silver per unit, but the pursuit of better performance increases it right back. Progress paradoxically consumes more silver, not less.

Similarly, the AI revolution is driving a shift to data centers that use 2-3x the silver of traditional servers. Goldman Sachs estimates data center power demand will grow 165% by 2030. If 50 GW of new AI capacity deploys by 2028, at 180 grams per AI server versus 60 grams for traditional servers, that’s an incremental 67.5 million ounces of new demand worth $3.375 billion.

There’s no substitute available at these specifications. When downtime costs $300,000 per hour and data integrity is mission-critical, you don’t experiment with materials that have a 6% conductivity gap. When data centers decommission servers every 3-5 years, recycling helps, but the 22% annual growth rate vastly exceeds the replacement rate.

Third: Demand growth cycles are simply faster than innovation cycles. This is the fundamental mismatch that explains why even aggressive optimization efforts struggle to keep pace. Copper plating required 20 years of R&D to reach commercial viability. Scaling to majority market share takes another 5-7 years. That’s a total timeline of 25+ years from concept to dominance.

Meanwhile, AI server deployments happen in 18 months, EV factory construction in 24 months, and solar installations in 6-12 months.

Compare the potential optimization savings (69 million ounces by 2028, if all targets are met) to the new demand being created:

AI data centers: +67.5 million ounces by 2028

EV incremental demand: +25-28 million ounces (20-30 million vehicles × 30g extra per EV)

5G/IoT infrastructure: +15-20 million ounces

Medical/healthcare growth: +3-4 million ounces

Total new demand being created: 110-120 million ounces by 2028.

Even if optimization efforts succeed in saving 69 million ounces, new applications are simultaneously adding 110-120 million ounces. The net gap is 40-50 million ounces of additional structural deficit annually, even assuming optimization targets are fully achieved.

Recycling is hitting physical limits. Total silver recycling reached a 12-year high of 193.9 million ounces in 2024 but year on year growth has not followed.

To significantly increase beyond 200 million ounces, the industry needs breakthroughs in recovering silver from dispersed applications like electronics e-waste, end-of-life solar panels (minimal recycling infrastructure exists today), and distributed industrial uses like switches, contacts, and bearings scattered across thousands of applications.

Why Silver Isn’t Lithium

Two fundamental characteristics distinguish silver from lithium, and explain why even aggressive industrial optimization may not cool prices.

First, the investment feedback loop. When industries optimize and save silver, investors interpret this as scarcity confirmation and buy more. Solar thrifting saves 45-55 million ounces, but investors absorb that slack. The 820 million ounce cumulative deficit has depleted COMEX stocks from 150 million ounces to 46 million ounces. Every ounce saved through optimization becomes available for investment hoarding rather than price relief. Lithium had no such dynamic; when battery makers reduced consumption, prices simply fell.

Second, the inelastic demand floor. Medical, aerospace, and mission-critical computing applications will pay any price. A silver wound dressing contains miniscule silver but prevents infections costing thousands of rupees. Aerospace certifications take years, and no engineer substitutes materials to save costs when aircraft safety is at stake. AI data centers won’t risk copper when downtime costs $300,000 per hour. These segments represent 10-15 million ounces that won’t fall regardless of price. Lithium faced no such constraint. Battery makers substituted to LFP chemistry when prices spiked.

Can Optimization Cool Silver Prices?

History offers both encouragement and caution. When silver last hit $49 in April 2011, industries responded aggressively. Solar manufacturers cut silver loading, fabrication demand decreased in 2012 despite continued installation growth, and silver intensity per panel roughly halved over the following decade. But 2011 was an investment bubble with the market actually in surplus. When speculative fever broke, prices crashed from $49 to under $26 in less than a month. Today’s situation is fundamentally different. An actual 820 million ounce cumulative deficit, structural supply constraints, and three mega-trends (AI, EVs, solar) accelerating simultaneously.

Industries are proving adaptation is possible. Solar’s 15-20% thrifting in a single year, copper plating reaching gigawatt-scale production, semiconductor fabs building recycling systems are commercial realities. The 2025 forecast showing solar’s first-ever demand decline proves that at $50 per ounce, industrial demand destruction happens.

The unknowns dominate: Will copper plating reach 50% market share by 2030 or stall at 20%? Will AI server growth match, exceed, or fall short of forecasts? Will recession materialize, and if so, will investment demand offset industrial weakness? Will recycling breakthroughs unlock 100+ million ounces in electronics waste? Will investors treat silver scarcity as a buying opportunity or exit signal? These variables won’t clarify until 2026-2027.

Until then, ReadOn!

Stellar breakdown of the demand dynamics. The lithium precedent you highlighted is crucial because itshows how quickly oversupply can materialize when prices incentivize new production. I rememer tracking lithium spot markets in 2022 and the shift from scarcity narrative to structural glut happened way faster than most analysts predicted. The key difference with silver is the byproduct constraint you mentioned which makes supply inelastic to price signals in the short run.

Very informative piece. I think it had a lot of calculations which can be improved. They just add some unnecessary cognitive load on the reader. I think when humans have no alternative - they innovate. The way scientist invented vaccine for COVID - in the same spirit this will be solved. Gone are the days when industry had to wait for over 2 decades to get a blue LED